A1 Riemann integral

Stein 책에는 리만적분에 대한 내용이 Appendix의 첫 장으로 되어 있다. 본문의 2장은 리만적분을 가정하고 진행하고 있으므로 이에 대한 보충설명이다.

가장 먼저는, 리만적분에 관한 기본적인 사실들을 인터넷으로 찾아보다가, nontrivial한 사실인 적분가능한 두 함수의 곱이 적분가능하다는 사실을 증명해보려고 했고, baby rudin의 6장을 다시 읽어보게 되었다. baby rudin은 Stieltjies 적분까지 포함한 논의를 하고 있어서 좀 복잡하지만, 그래도 찬찬히 읽어보니 필요한 내용을 다 정리할 수 있겠다 싶었다. 그런데 Stein의 2장을 계속 읽다보니 해당 책의 Appendix의 1장 (이상 Stein A1)에 해당 내용이 정리되어있다는 걸 보고 거길 읽어보았다. Stein A1이 훨씬 간결하게, 꼭 필요한 내용들만 있는데다가, 기본적으로 Rudin 책의 내용과 거의 비슷하기 때문에, Stein A1을 정리하려고 한다.

Appendix 1. Riemann Integral

Appendix 1은 두 개의 절로 되어 있다.

- Basic properties

- Sets of measure zero and discontinuities of integrable functions

그 중 1절이 시작되기에 앞서, 기본적인 개념이 정의된다. 가장 먼저 나오는 건 당연히 partition이다. 뒤에서 partition에 점을 추가하거나 둘을 합치거나 공통된 부분을 구하는 과정이 꽤 자주 나온다. 그래서, partition을 tuple로 정의하고, 이 tuple에 대한 교집합과 합집합을 정의해보았다. partition을 tuple로 정의하는 경우에 주의할 점은, open interval과 partition을 잘 구분해서 표현해야 한다는 점이다. 하지만 그 구분만 잘 될 수 있다면, 괜찮은 notation이지 않나 하는 생각이다. 다음으로는 upper limit과 lower limit이 정의되고, 이로부터 적분가능성과 리만적분이 정의된다.

A partition $P$ of $[a,b]$ is a sequence where

\[a=x_0\lt x_1\lt\cdots\lt x_{N-1}\lt x_N=b.\]Denote $P$ by a tuple

\[\begin{aligned} P &=(x_0,x_1,\cdots,x_{N-1},x_N)\\ &=\left(x_j:j=0,\cdots,N\right) \end{aligned}\]We can take union or intersection on a pair of partitions $P_1$ and $P_2$ by taking union or intersection on the sets points in the partitions and then enumerate the points in increasing order. For example, if $P_1=(1,3,5,6,8)$ and $P_2=(1,2,5,6)$ are two partitions,

\[\begin{aligned} P_1\cup P_2&=(1,2,3,5,6,8)\\ P_1\cap P_2&=(1,5,6) \end{aligned}\]Let $f:[a,b]\to\mathbb R$ be bounded and let $P$ be a partition of $[a,b]$. The upper sum $\mathcal U(f,P)$ and lower sum $\mathcal L(f,P)$ of $f$ with respect to $P$ are

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f,P) &=\sum_{j=1}^N\sup\{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j\}(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ \mathcal L(f,P) &=\sum_{j=1}^N\inf\{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j\}(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ \end{aligned}\]The supremum and the infimum always exist since $f$ is bounded. It is immediate that $\mathcal U(f,P)\ge\mathcal L(f,P)$.

Definition

$f$ is said to be (Riemann) integrable if for every $\epsilon\gt0$, there exists $P$ such that

\[(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P)\lt\epsilon.\]Here, we denote $(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P)=\mathcal U(f,P)-\mathcal L(f,P)$ for brevity.

If another partition $P’$ of $[a,b]$ is a subset of $P$ where we conceive $P$ and $P’$ as sets, then $P’$ is called a refinement of $P$.

Proposition

If $P’$ is a refinement of $P$, then $\mathcal U(f,P’)\le\mathcal U(f,P)$ and $\mathcal L(f,P’)\ge\mathcal L(f,P)$.

proof It suffices to observe the effect of adding a point to a partition $P$ since $P’$ can be obtained by adding finite points to $P$. We are to prove $\mathcal U(f,P’)\le\mathcal U(f,P)$. Let $P=(x_0,\cdots,x_N)$ be a partition and let $P’=P\cup(c)$ where $c\in[a,b]$. If $c=x_j$ for some $j$, then $P’=P$ and the inequalities follows trivially. Suppose now that $x_{i-1}\lt c\lt x_i$ for some $i\in\{1,\cdots,N\}$. Then

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f,P') &=\sum_{j\ne i}\sup_{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}(x_j-x_{j-1})+\sup_{f(x):x_{i-1}\le x\le c}(c-x_{i-1})+\sup_{f(x):c\le x\le x_j}(x_j-c)\\ &\le\sum_{j\ne i}\sup_{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}(x_j-x_{j-1})+\sup_{f(x):x_{i-1}\le x\le x_i}(c-x_{i-1})+\sup_{f(x):x_{i-1}\le x\le x_i}(x_j-c)\\ &=\sum_{j\ne i}\sup_{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}(x_j-x_{j-1})+\sup_{f(x):x_{i-1}\le x\le x_i}(x_i-x_{i-1})\\ &=\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{f(x):x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=\mathcal U(f,P) \end{aligned}\]Similarly, $\mathcal L(f,P’)\ge\mathcal L(f,P)$ holds for the same $P$ and $P’$. QED

Let

\[U=\inf_P\,\mathcal U(f,P),\quad L=\sup_P\,\mathcal L(f,P).\]Such $U$ and $L$ always exist since $f$ is bounded. Moreover,

Proposition

$f$ is integrable if and only if $U=L$.

proof Suppose the former. It is trivial that $U\ge L$. Fix $\epsilon\gt0$. Since $f$ is integrable, there exists a partition $P$ such that

\[\mathcal U(f,P)-\mathcal L(f,P)\lt\epsilon\]Then

\[\begin{aligned} U-L &=\inf_P\,\mathcal U(f,P)-\sup_P\,\mathcal L(f,P)\\ &\le\mathcal U(f,P)-\mathcal L(f,P)\\ &\lt\epsilon \end{aligned}\]Since $\epsilon$ was arbitrary, $U\le L$.

Suppose the latter and fix $\epsilon\gt0$. There exist $P_1$ and $P_2$ such that

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f,P_1) - U\lt\frac\epsilon2\\ L - \mathcal L(f,P_2)\lt\frac\epsilon2 \end{aligned}\]Let $P$ be the common refinement of $P_1$ and $P_2$, the enumeration of the intersection of $P_1$ and $P_2$ as sets. Then

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f,P) - \mathcal L(f,P) &\le\mathcal U(f,P_1) - \mathcal L(f,P_2)\\ &\lt U-L+\epsilon\\ &=\epsilon. \end{aligned}\]Thus $f$ is integrable as desired. QED

Definition

If $f$ is integrable so that $U=L$, define

\[\int_a^bf(x)\,dx=U=L\]For brevity, we somtimes write $\int_a^bf\,dx$ or $\int f$ instead. For complex functions, we have the following definition

Definition

$f:[a,b]\to\mathbb C$ is such that $f=u+iv$, then $f$ is integrable on $[a,b]$ if both of $u$ and $v$ are integrable on $[a,b]$ and

\[\int_a^bf(x)\,dx=\int_a^bu(x)\,dx+i\int_a^bv(x)\,dx\]It is a fundamental fact that

Proposition

if $f$ is continuous on $[a,b]$, then $f$ is integrable.

proof Suppose that $f$ is real valued. Since $[a,b]$ is compact (closed and bounded), $f$ is uniformly continuous on this interval. That is, for each $\epsilon\gt0$, there exists $\delta\gt0$ such that

\[|x-y|\lt\delta\quad\Longrightarrow\quad |f(x)-f(y)|\lt\frac\epsilon{b-a}.\]Choose $n$ so that $\frac{b-a}N\lt\delta$ and let

\[P=\left(a, a+\frac{b-a}N, a+2\frac{b-a}N, \cdots, a+(N-1)\frac{b-a}N,b\right).\]Then

\[\begin{aligned} (\mathcal U - \mathcal L)(f, P) &=\sum_{j=1}^N\left( \sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x) - \inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x) \right)\frac{b-a}N\\ &\le\sum_{j=1}^N\frac\epsilon{b-a}\frac{b-a}N=\epsilon. \end{aligned}\]Thus $f$ is integrable.

Suppose now that $f$ is complex valued so that $f=u+iv$. Since $f$ is continuous, it is trivial that $u$ and $v$ are also continuous. It follows that $u$ and $v$ are both integrable and that $f$ is integrable. QED

A1.1 Basic properties

책에는 Proposition 1.1에서 $f$와 $g$가 적분가능하면 $f+g$와 $cf$가 적분가능하다는 사실이 먼저 나오고, 그 이후에 Lemma 1.2로 연속함수의 합성에 의한 효과가 언급되며, 그 직후에 $fg$, $|f|$도 적분가능하다는 사실이 설명되고 있다. 그런데 $fg$, $|f|$가 적분가능하다는 사실은 $f+g$, $cf$가 적분가능하다는 사실만큼이나 중요하다고 생각되고 lemma의 증명에 proposition의 결과가 필요해보이지 않아서 lemma를 앞으로 빼고 proposition을 뒤로 넣었다. baby Rudin의 6장도 이 순서로 되어 있다. 그리고 lemma, proposition 등의 넘버링은 원래 1.1, 1.2 와 같이 되어 있었지만 이 포스트에서는 Appendix 1의 내용만 쓸 것이므로 1, 2 와 같이 썼다.

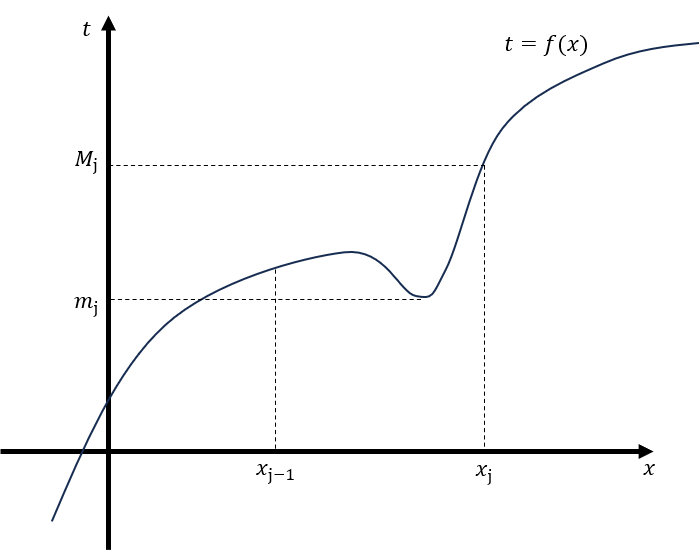

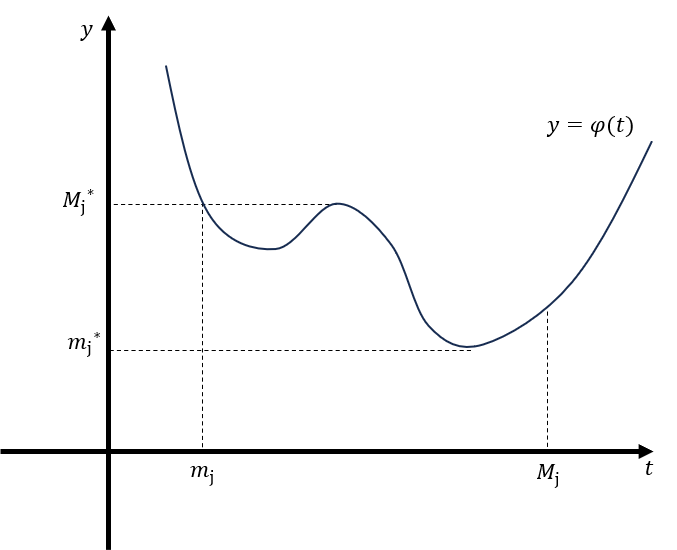

lemma 1의 Stein 증명이 잘 이해가 안가서 Rudin의 증명을 더 많이 봤는데, 기본적으로 두 증명이 거의 같다. notation은 두 증명을 적당히 조합해서 썼다. 증명은, $\phi\circ f$에 대한 upper-lower limit의 차가 $\epsilon$의 배수보다 적어짐을 보이기 위하는 것이 목적이다. $\phi$의 uniform continuity로부터 $\delta$를, $f$의 적분가능성으로부터 $P$를 얻어내고, 각 subinterval에 대하여 $f$의 최댓값 $M_j$과 최솟값 $m_j$의 차이가 $\delta$와 비교했을 때 큰지($j\in A$) 작은지($j\in B$)로 나누어 생각한다. 만약 $j\in A$이면 $\phi\circ f$의 최댓값 $M^\ast_j$과 최솟값 $m^\ast_j$의 차이가 $\epsilon$의 상수배보다 적어져서 쉽게 해결된다. 만약 $j\in B$이면 $M_j-m_j\ge\delta$라는 사실로부터 $\sum_{j\in B}(x_j-x_{j-1})$가 $\epsilon$의 상수배보다 적다는 것을 $P$의 construction으로부터 얻어내어 해결한다. 둘을 조합하면 증명이 완성된다.

Lemma 1

Suppose that $f:[a,b]\to\mathbb R$ is integrable and that $\phi:\mathbb R\to\mathbb R$ is continuous. Then, $\phi\circ f:[a,b]\to\mathbb R$ is integrable.

proof Since $f$ is bounded, $m\le f\le M$ on $[a,b]$ for some real $m$ and $M$. Since $\phi$ is continuous, its range on $[m,M]$ is bounded ; $\lvert\phi\rvert\le K$ on $[m,M]$ for some $K\ge0$. Fix $\epsilon\gt0$. Since $\phi$ is uniformly continuous on $[m,M]$, there exists $\delta\gt0$ such that $\delta\lt\epsilon$ and

\[m\le s,t\le M,\quad |s-t|\lt\delta\quad\Longrightarrow\quad\lvert\phi(s)-\phi(t)\rvert\lt\epsilon. \tag{1-1}\]Since $f$ is integrable, there exists a partition $P=(x_0,x_1,\cdots,x_N)$ of $[a,b]$ so that

\[\mathcal U(f, P)-\mathcal L(f, P)\lt\delta^2. \tag{1-2}\]For each $j$, denote

\[\begin{aligned} M_j&=\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)&m_j&=\inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)\\ M^\ast_j&=\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}\phi\circ f(x)&m^\ast_j&=\inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}\phi\circ f(x). \end{aligned}\]These values exist since $f$ is bounded and $\phi$ is continuous. Then, by (1-2),

\[\sum_{j=1}^N(M_j-m_j)(x_j-x_{j-1})\lt\delta^2 \tag{1-3}\]Let $A=\{j:M_j-m_j\lt\delta\}$ and $B=\{j:M_j-m_j\ge\delta\}$. If $j\in A$, then $M^\ast_j-m^\ast_j\le\epsilon$ by (1-1). If $j\in B$, then we can use (1-3) to get

\[\sum_{j\in B}(x_j-x_{j-1})\lt\delta\]and we also have $\lvert M^\ast_j-m^\ast_j\rvert\le 2K$. Therefore,

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(\phi\circ f, P)-\mathcal L(\phi\circ f, P) &=\sum_{j=1}^N(M^\ast_j-m^\ast_j)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=\sum_{j\in A}(M^\ast_j-m^\ast_j)(x_j-x_{j-1})+\sum_{j\in B}(M^\ast_j-m^\ast_j)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &\le\epsilon\sum_{j\in A}(x_j-x_{j-1})+2K\sum_{j\in B}(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &\le\epsilon\sum_{j=1}^\infty(x_j-x_{j-1})+2K\delta\\ &\le\epsilon\left[(b-a)+2K\right] \end{aligned}\]Since $\epsilon$ was arbitrary, $\phi\circ f$ is integrable. QED

Proposition 2

Suppose that $f$ and $g$ are integrable function on $[a,b]$. Then

- $f+g$ is integrable and $\int_a^b(f+g)\,dx=\int_a^bf\,dx+\int_a^bg\,dx$.

- If $c$ is a constant, then $cf$ is integrable and $\int_a^bcf\,dx=c\int_a^bf\,dx$.

- If $f$ and $g$ are both real valued and if $f\le g$, then $\int_a^bf\,dx\le\int_a^bg\,dx$.

- If $a\le c\le b$, then $\int_a^bf\,dx=\int_a^cf\,dx+\int_c^bf\,dx$.

- $fg$ is integrable.

- $\lvert f\rvert$ is integrable and $\lvert\int_a^b f\,dx\rvert\le \int_a^b\lvert f\rvert\,dx$.

Proposition 2의 (f)의 경우 Rudin의 증명은 천재적이다. 그 말은, 나로서는 직관적으로 와닿지는 않는다는 말이다. 아마도 RCA에서도 비슷한 부등식에 대한 Rudin의 증명이 비슷한 방식이었던 것 같은데, 간결하기는 하고 멋있긴 한데 내가 소화하기에는 좀 과하다. 내 수준의 elementary한 증명으로 넣었고 이건 Stein의 힌트를 따른 것이기도 하다.

Suppose first that $f$ and $g$ are real valued. Fix $\epsilon\gt0$. Since $f$ and $g$ are integrable, there exist $P_1$ and $P_2$ such that

\[\begin{align*} (\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P_1)&\lt\frac\epsilon2\\ (\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(g,P_2)&\lt\frac\epsilon2 \end{align*}\]Take $P=P_1\cap P_2=(x_0,x_1,\cdots,x_N)$. Since $P$ is finer than $P_1$ and $P_2$,

\[\begin{align*} (\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P)&\lt\frac\epsilon2\\ (\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(g,P)&\lt\frac\epsilon2 \tag{2-1} \end{align*}\]Thus,

\[\begin{align*} (\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f+g,P) &=\sum_{j=1}^N\left( \sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}\left(f(x)+g(x)\right) - \inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}\left(f(x)+g(x)\right) \right)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &\le\sum_{j=1}^N\left( \sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)+\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}g(x) - \inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)-\inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}g(x) \right)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=\sum_{j=1}^N\left( \sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x) - \inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x) \right)(x_j-x_{j-1}) +\sum_{j=1}^N\left( \sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}g(x) - \inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}g(x) \right)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P)+(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(g,P)\\ &\lt\epsilon \end{align*}\]Thus $f+g$ is integrable.

With the same $P$ corresponding to $\epsilon\gt0$, we can use (2-1) again to get

\[\mathcal U(f,P)\le\mathcal U(f,P)-\mathcal L(f,P)+\int f\,dx\lt\int f\,dx+\frac\epsilon2.\]Similarly,

\[\mathcal U(g,P)\lt\int g+\frac\epsilon2.\]By the subadditivity of the supremum as just before,

\[\begin{aligned} \int f+g &\le\mathcal U(f+g,P)\\ &\le\mathcal U(f,P)+\mathcal U(g,P)\\ &\lt\int f+\int g+\epsilon. \end{aligned}\]Since $\epsilon$ was arbitrary, $\int f+g\le\int f+\int g.$ Similarly, we can use $\mathcal L$ instead of $\mathcal U$ to get $\int f+g\ge\int f+\int g$ and thus

\[\int f+g=\int f+\int g.\]Now suppose that $f$ and $g$ are complex valued so that $f=f_R+if_I$ and $g=g_R+ig_I$. If $f$ and $g$ are both integrable, $f_R$, $f_I$, $g_R$ and $g_I$ are all integrable. It follows that $f_R+g_R$ and $f_I+g_I$ are both integrable and that

\[f+g=(f_R+g_R)+i(f_I+g_I)\]is integrable. Moreover

\[\begin{align*} \int f+g &=\int (f_R+g_R)+i(f_I+g_I)\\ &=\int (f_R+g_R)+i\int(f_I+g_I)\\ &=\int f_R+\int g_R+i\int f_I+i\int g_I\\ &=\int f+\int g \end{align*}\] \[\begin{aligned} \int_a^bcf(x)\,dx &=\inf_P\,\mathcal U(cf,P)\\ &=\inf_P\,\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}cf(x)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=c\inf_P\,\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=c\inf_P\,\mathcal U(f,P)\\ &=c\int_a^bf(x)\,dx. \end{aligned}\] \[\begin{aligned} \int_a^bf(x)\,dx &=\inf_P\,\mathcal U(f,P)\\ &=\inf_P\,\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &\le\inf_P\,\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}g(x)(x_j-x_{j-1})\\ &=\inf_P\,\mathcal U(g,P)\\ &=\int_a^bg(x)\,dx \end{aligned}\]Fix $\epsilon$.

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f, P_1)&\lt\int_a^cf\,dx+\frac\epsilon2\\ \mathcal U(f, P_2)&\lt\int_c^bf\,dx+\frac\epsilon2 \end{aligned}\]for a partition $P_1$ of $[a,c]$ and a partition $P_2$ of $[c,b]$. $P=P_1\cup P_2$ is a partition of $[a,b]$ and $ \mathcal U(f,P_1)+\mathcal U(f,P_2)=\mathcal U(f,P) $ by the definition of $\mathcal U$. Thus,

\[\int_a^bf\,dx\le\mathcal U(f,P)=\mathcal U(f,P_1)+\mathcal U(f,P_2)\lt\int_a^cf\,dx+\int_c^bf\,dx+\epsilon.\]Since $\epsilon$ was arbitrary,

\[\int_a^bf\,dx\le\int_a^cf\,dx+\int_c^bf\,dx.\]An analogous argument can be applied to $\mathcal L$ instead of $\mathcal U$ so that the converse inequality also holds. Therefore

\[\int_a^bf\,dx=\int_a^cf\,dx+\int_c^bf\,dx.\]By (b), $-g$ is integrable. By (a), both of the $f+g$ and $f-g$ are integrable. Apply Lemma 1 where $\phi(t)=t^2$. Then, both of the $(f+g)^2=\phi\circ(f+g)$ and $(f-g)^2=\phi\circ(f-g)$ are integrable. Apply (a) and (b) again to concluce that

\[fg=\frac14\left[(f+g)^2-(f-g)^2\right]\]is integrable.

Apply Lemma 1 where $\phi(t)=\lvert t\rvert$.

Apply (c). Since $|f|\ge f$ and $|f|\ge-f$, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \int_a^b|f|\,dx&\ge\int_a^bf\,dx\\ \int_a^b|f|\,dx&\ge-\int_a^bf\,dx. \end{aligned}\]Therefore, (f) follows.

Proposition 3 If $f:[a,b]\to\mathbb R$ is bounded and monotonic, then $f$ is integrable.

proof Suppose first that $f$ is monotonically increasing. For an integer $N\gt0$, let $P_N$ be a uniform partition on $[a,b]$ ;

\[P_N=\left(a+j\frac{b-a}n:n=0,1,\cdots,N\right)\]Then,

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal U(f,P_N)&=\sum_{j=1}^Nf(x_j)\frac{b-a}N\\ \mathcal L(f,P_N)&=\sum_{j=1}^Nf(x_{j-1})\frac{b-a}N \end{aligned}\]so that

\[(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P_N)=\left(f(b)-f(a)\right)\frac{b-a}N.\]Thus, when $\epsilon\gt0$ is given, we can choose $N$ so that $\left(f(b)-f(a)\right)\frac{b-a}N\lt\epsilon$ to conclude that $(\mathcal U-\mathcal L)(f,P_N)\lt\epsilon$.

Suppose now that $f$ is monotonically decreasing. Then $-f$ is a monotonically increasing function and is integrable. Therefore, $f$ is integrable too.

Proposition 4 Suppose that $f$ is a bounded function on $[a,b]$, that $a\lt c\lt b$ and that for any $\delta\gt0$ such that $\delta\lt\max\{c-a,b-c\}$, $f$ is integrable both on $[a,c-\delta]$ and $[c+\delta,b]$. Prove that $f$ is integrable on $[a,b]$.

proof Suppose first that $f$ is real valued. Since $f$ is bounded, $\lvert f\rvert\le M$ for some $M$. Fix $\epsilon\ge0$. Choose $\delta\gt0$ so that $2M\cdot2\delta\lt\frac\epsilon3$ and $\delta\lt\max\{c-a,b-c\}$. Choose two partitions $P_1$ on $[a, c-\delta]$ and $P_2$ on $[c+\delta,b]$ so that

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\mathcal U-\mathcal L\right)(f,P_1)&\lt\frac\epsilon3\\ \left(\mathcal U-\mathcal L\right)(f,P_2)&\lt\frac\epsilon3 \end{aligned}\]Then $P=P_1\cup P_2$ is a partition on $[a,b]$ and

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\mathcal U-\mathcal L\right)(f,P) =&\left(\mathcal U-\mathcal L\right)(f,P_1)+\left(\mathcal U-\mathcal L\right)(f,P_2)\\ &+\left( \sup_{c-\delta\le x\le c+\delta}f(x) - \inf_{c-\delta\le x\le c+\delta}f(x) \right)\times2\delta\\ \lt&\frac\epsilon3+\frac\epsilon3+2M\times2\delta\\ \le&\epsilon. \end{aligned}\]Therefore, $f$ is integrable on $[a,b]$.

Suppose now that $f$ is complex valued so that $f=u+iv$. For any $\delta\gt0$ such that $\delta\lt\max\{c-a,b-c\}$, $u$ and $v$ are integrable both on $[a,c-\delta]$ and $[c+\delta,b]$. Thus $u$ and $v$ are integrable on $[a,b]$ and so is $f$. QED

$f$ is a function on the unit circle if it is a $2\pi$-periodic function on $\mathbb R$.

Lemma 5 Suppose that $f$ is a function on the unit circle, that $f$ is integrable on $[-\pi,\pi]$ and $B=\sup\lvert f\rvert$. Then, there exists a sequence $\{f_k\}_{k=1}^\infty$ of continuous functions $f_k$ on the unit circle such that $\sup\lvert f_k\rvert\le B$ for all $k$ and that

\[\lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert f-f_k\rvert\,dx=0.\]너무나도 간단한 종류의 lemma이다. 그런데 이걸 증명하는 데 왜 오래 걸렸을까.

Stein의 증명은 따라가기 싫었다. 불연속함수에 대해서는 아직 적분이 정의될 수 없는데 마치 정의된 것처럼 쓰고 있다. 그렇다면 그렇게 notation abusing이 일어난 부분에 대해서는 적절히 독자가 판단하리라고 생각한 것 같은데, 그렇게 하기가 싫었다. 그래서 혼자 증명해본 것이지만, Stein의 증명과 그 형태는 거의 같다.

step function($=f^\ast$)으로 원래 함수를 approximate할 수 있다는 건 당연하다. 르벡적분에서도 항상 하던거다. 그런데 이 step function이 연속이 아니니까 연속으로 만들어주는 과정이 있고, 만들어진 연속함수($f_k$)가 approximation 조건을 만족하는지만 따지면 되는 것인데, 그건 $\delta$를 작게 잡으면 boundedness로부터 당연히 해결될 문제라 근본적으로 너무 쉬운 문제이다. 상세한 사항들을 일일이 적으려 하다 보니 오래 걸린 것 같다. 그 상세한 사항들이 맞는지 확인하는 것은 물론 중요하지만, 그렇게 꼼꼼히 따지는 과정에서 오히려 해결고자 하는 목적에 온전히 힘을 쏟지 못한 느낌이다.

$f$가 실함수일 때에 대해서는 다 증명이 되었고, 복소함수일 때도 주요한 점은 증명이 되었지만 $\lvert f_k\rvert\le B$의 증명이 잘 안된다. bounded인 건 분명한데 upper bound를 $B$로 잡을 수 있는지 모르겠다. 아니 잡을 수 있을 것 같은데, 증명방법을 모르겠다. 이 부분은 미완성으로 남겨놓은 채 일단 넘어가려고 한다. 여하튼, 이것으로 A1의 1절은 마친 셈이 되었다.

Note that $f(-\pi)=f(\pi)$. Suppose first that $f$ is real valued.

Fix a positive integer $k$. There exists a partition $P_k=(x_0,\cdots,x_N)$ on $[-\pi,\pi]$ such that $\mathcal U(f,P_k) - \mathcal L(f,P_k)\lt\frac1{2k}$. Write

\[\begin{align*} M_j&=\sup_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x)\\ m_j&=\inf_{x_{j-1}\le x\le x_j}f(x) \end{align*}\]Then

\[\sum_{j=1}^N(M_j-m_j)(x_j-x_{j-1})\lt\frac1{2k}. \tag{5-1}\]

Make a step function $f^\ast$ on $[-\pi,\pi)$ defined by

\[f^\ast(x) = M_j. \quad\text{if}\quad x_{j-1}\le x\lt x_j\]Note that $f^\ast$ is not continuous. Choose $\delta\gt0$ such that $4NB\delta\lt\frac1{2k}$ and $\delta\lt\min\left\{\frac{x_j-x_{j-1}}2 : j=1,\cdots,N\right\}$. Relax $f^\ast$ at each point $x_j$ to make it continuous by defining $f_k$ on $[-\pi,\pi)$ as

\[f_k(x)= \begin{cases} M_j &\text{if}\quad x_{j-1}+\delta\le x\lt x_j-\delta\quad\text{for}\quad j=1,\cdots,N\\[10pt] \frac{M_{j+1}-M_j}{2\delta}(x-x_j)+\frac{M_j+M_{j+1}}2 &\text{if}\quad x_j-\delta\le x\lt x_j+\delta\quad\text{for}\quad j=1,\cdots,N-1\\[10pt] \frac{M_1-M_N}{2\delta}(x-x_0)+\frac{M_N+M_1}2 &\text{if}\quad x_0\le x\lt x_0+\delta\quad\\[10pt] \frac{M_1-M_N}{2\delta}(x-x_N)+\frac{M_N+M_1}2 &\text{if}\quad x_N-\delta\le x\lt x_N \end{cases}\]

Let $\tilde P_k=(x_j-\delta:j=1,\cdots,N)\cup(x_j+\delta:j=0,\cdots,N-1)$. Then, by (5-1) and the related conditions above,

\[\begin{aligned} \int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert f-f_k\rvert\,dx \le&\;\mathcal U\left(\lvert f-f_k\rvert, \tilde P_k\right)\\ =&\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}+\delta\le x\le x_j-\delta}\lvert f(x)-f_k(x)\rvert(x_j-x_{j-1}-2\delta)\\ &+\sum_{j=1}^{N-1}\sup_{x_j-\delta\le x\le x_j+\delta}\lvert f(x)-f_k(x)\rvert\cdot2\delta\\ &+\sup_{x_0\le x\le x_0+\delta}\lvert f(x)-f_k(x)\rvert\cdot\delta +\sup_{x_N-\delta\le x\le x_N}\lvert f(x)-f_k(x)\rvert\cdot\delta\\ \lt&\sum_{j=1}^N\sup_{x_{j-1}+\delta\le x\le x_j-\delta}\lvert f(x)-M_j\rvert(x_j-x_{j-1}) +2B\cdot2\delta\cdot(N-1)+2\delta B+2\delta B\\ \lt&\frac1{2k}+4NB\delta\\ \lt&\frac1k \end{aligned} \tag{5-2}\]The domain of so defined $f_k$ can be extended to $\mathbb R$ by making it $2\pi$-periodic and it is bounded by $B$ by the construction of $f_k$. Finally, the limit of the right hand side of (5-2) converges to $0$ as $k\to\infty$ by the comparison test.

Suppose now that $f$ is complex valued so that $f=u+iv$. Then both of the $u$ and $v$ are functions on the unit circle and integrable on $[-\pi,\pi]$. There exist $\{u_k\}_1^\infty$ and $\{v_k\}_1^\infty$ continuous on the unit circle such that

\[\begin{aligned} \lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert u-u_k\rvert\,dx&=0\\ \lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert v-v_k\rvert\,dx&=0\\ \end{aligned}\]Thus

\[\begin{aligned} \lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert f-f_k\rvert\,dx &=\lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert(u-u_k)+i(v-v_k)\rvert\,dx\\ &\le\lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert u-u_k\rvert\,dx+\int_{-\pi}^\pi\lvert v-v_k\rvert\,dx\\ &=0. \end{aligned}\]A1.2 Sets of measure zero and discontinuities of integrable functions

이 절에서는 Riemann integrable function의 characterization을 불연속성을 가지고 서술한다. 즉, 어떤 함수 $f$가 integrable이기위한 필요충분조건은, 불연속점들의 집합의 measure가 0이라는 정리를 증명한다. 재밌는 것은, 이런 논의를 위해서 measure를 정의하지는 않는다는 것이다. 르벡 measure를 구간에 적용하면 그 구간의 길이가 되므로, 구간의 길이만으로만 measure zero set을 정의하고 있다.

정리의 증명 전에 osc라는 함수를 정의한다. 이것을 요동(perturbation)이라고 번역하면 적절할까. (사실 적절한 한국어 표현이 기억났었는데, 노트북의 와이파이가 끊기는 바람에 사고의 흐름도 같이 끊어졌다.) $\text{osc}(f,c)$는 어떤 함수가 어떤 점에서 얼마나 요동치느냐하는 값을 나타낸다. 그리고 이로부터 함수 $f(x)$가 $x=c$에서 연속이기 위한 필요충분조건이 $\text{osc}(f,c)=0$임을 언급한다.

정리의 증명에 핵심이 되는 것은 lemma 8이라고 하는데, 여기에서는 집합 $A_\epsilon=\{c:\text{osc}(f,c)\ge\epsilon\}$이 compact하다는 사실을 증명한다고 한다.

댓글남기기